Something must have happened.

The world shifted on its orbit, perhaps; the polarity of our planet reversed; the sky fallen…

Michael Gove has tinkered with the GCSE syllabus (no change there then!) but has done it with… wait for it… some degree of consultation and for year groups not currently half way through their course! I’m almost grateful for this! And feel guilty!

Is this what Stockholm Syndrome feels like?

So there are various sources of information linked below:

The TES

Ofqual

The BBC and

the DfE

So, my first question is: when do these reforms take place?

They are described for first teaching in 2015 (at least for English Literature and English Language and Maths) which would mean when our current Year 8s hit Year 10, they will be subject to these. Twenty months to go.

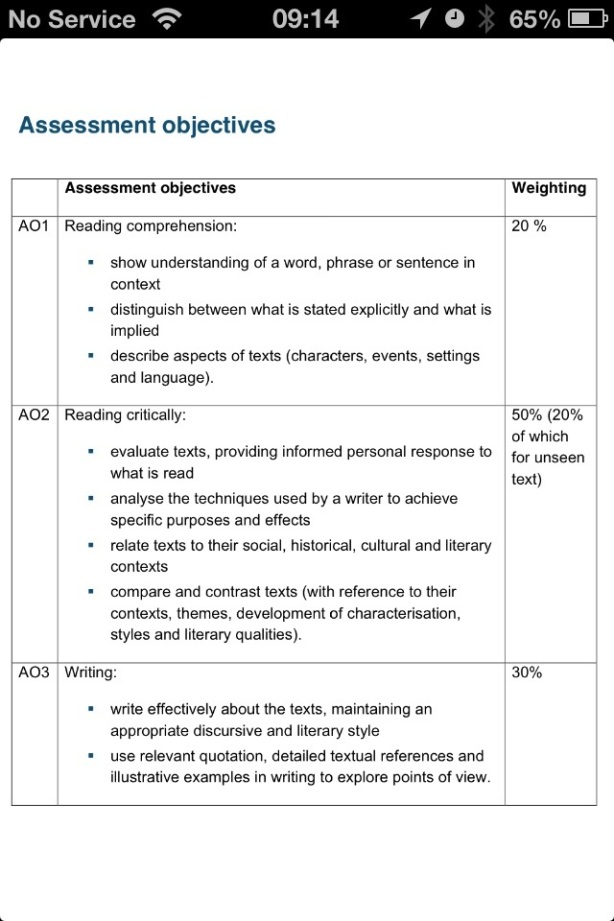

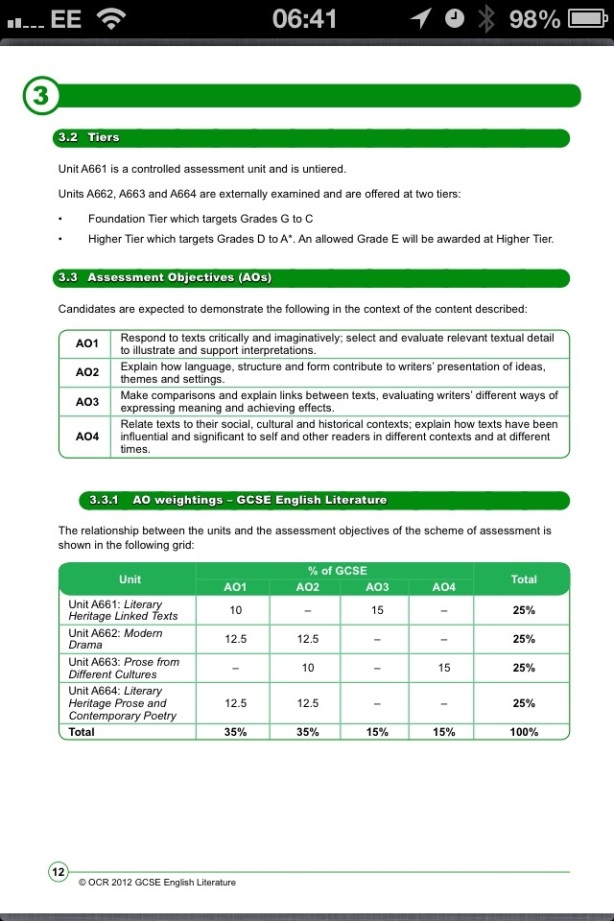

Grades will be replaced with numerical .. well… numerical grades I suppose. The current 8 pass grades of A*-G will be replaced with 9 pass grades of 1-9. I see nothing terribly objectionable in that… but also nothing terribly constructive. I don’t see the point. Why? It replaces one arbitrary ladder with another. Are we meant to believe that schools will not simply replace the C/D border trauma with an equally traumatic 5/6 border – or whichever grades become synonymous with that border.

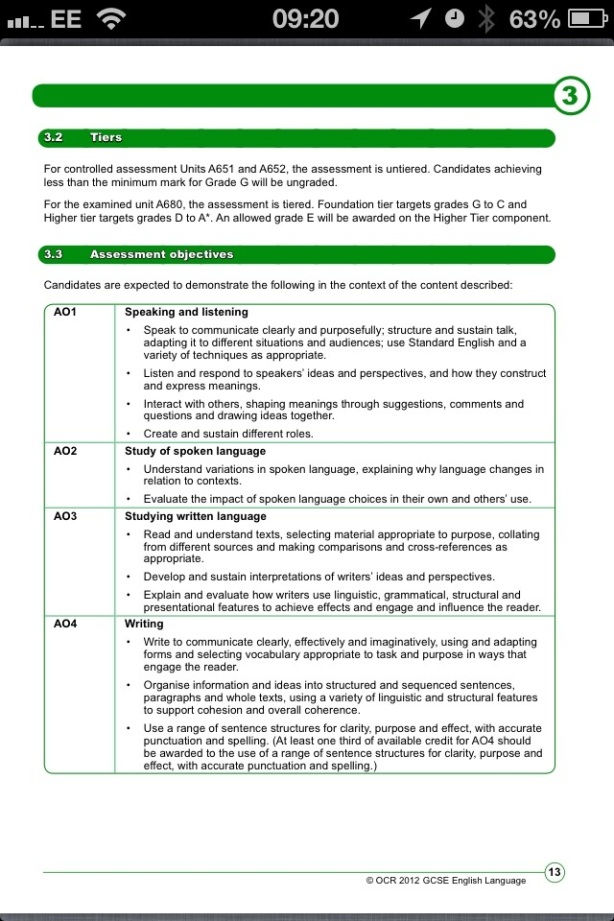

Tiered exams will disappear. Ok. Again, no massive issues in principle if I have confidence that the exam boards have the ability to set questions which genuinely challenge the most able to differentiate between the 9s and 8s and give the 1s and 2s a fair chance. And if I have confidence that a marker will be able to give full credit to the full range of marks. And I should have that confidence – after all, we as teachers are doing it day-in day-out – but, after the last two years’ results, I’m sorry but I just don’t.

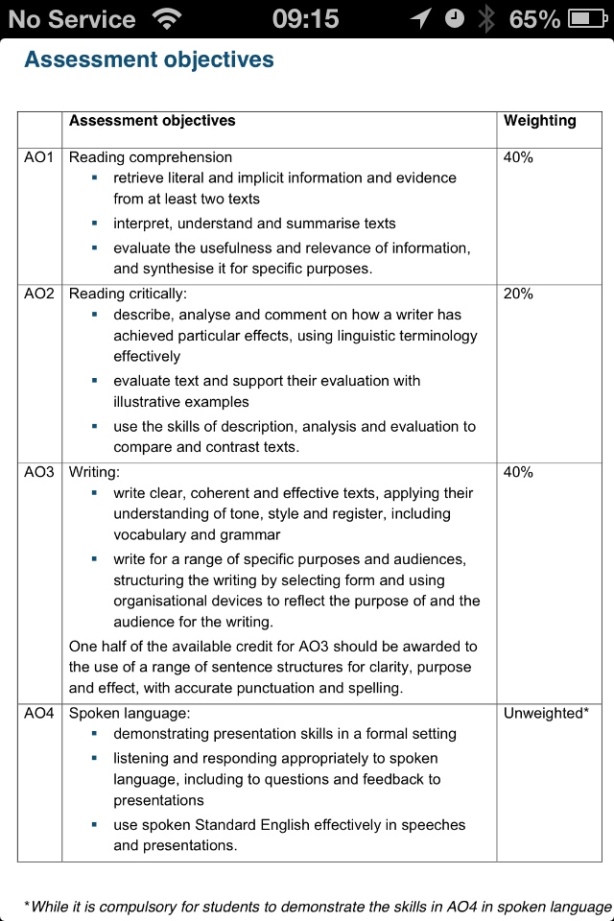

Coursework and Controlled Assessments are removed in favour of a 100% terminal exam.

Now, this I do object to!

English is not apt for exams in my humble opinion. The key processes of reading and writing – by their very nature – are slow and ruminative and reflective. I spend time teaching kids to craft each sentence, to carefully make lexical choices, to control their writing, to balance control with a certain responsiveness to the text which they are creating.

For heaven’s sake, I even review, amend and redraft text messages before I send them!

To force either creative or analytical responses in – let’s say – forty-five minutes will not result in either careful or thoughtful or effective writing. What it will result in is content-led teaching in Literature where “the book” is taught rather than the skills of reading. Feature spotting. Writing toolkits. Similes shoehorned in; metaphors wrenched out of shape; alliteration abounding out of control. Skills demonstrated with no real understanding of whether they work or not.

It has been an eye opener doing coursework for the iGCSE alongside CAs for OCR GCSE and C/D students in controlled assessments are producing C/B quality work as coursework. I know there’s the risk that parents give undue help. But – notice the carefully chosen co-ordinating conjunction to open the sentence because it ‘fits’ with my current and somewhat conversational tone even though “However” might be more technically correct – you see, I think like this! – But some kids will just work better at home with nagging parents and away from other kids.

What other changes will we see?

More “whole book” testing. How can that be consistent with exam situations?

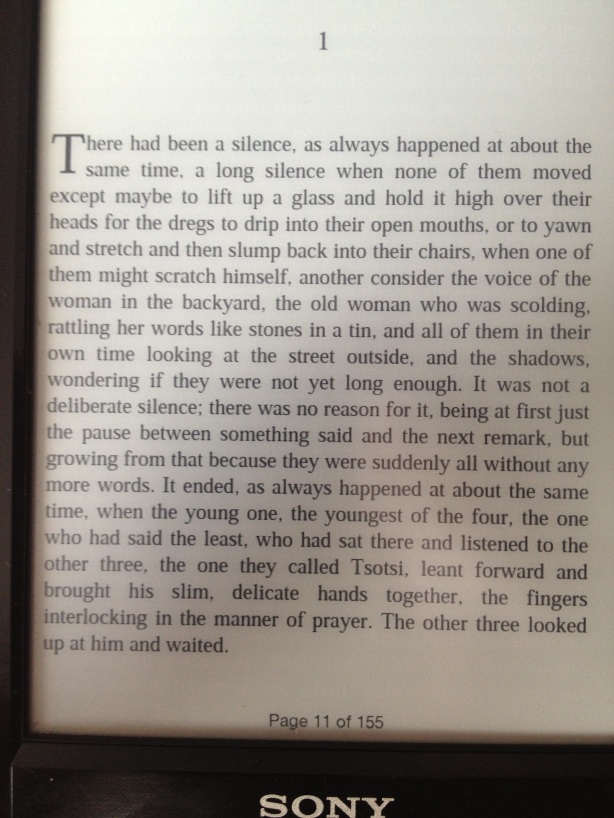

More 19th century novels and Romantic poetry. Well, fair enough! There’s great stuff there. Blake remains my favourite poet! But there’s a treasure trove of modern literary gems: Purple Hibiscus, Things Fall Apart, Mister Pip, Tsotsi. Yes, I do have a penchant for post-colonial literature! And I fear from the information released thus far that the curriculum is increasingly like the government: white, male, middle class, bound to the safety of the ‘classics’ and worryingly Anglo-centric!

And why is it that every time the BBC report an education article they use the same picture of the same exam hall every time?